Part 1: What is vectorisation?

In the last example you compiled and compared two loops. The first was a standard loop;

for (int i=0; i<size; ++i)

{

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}while the second was a vectorised loop

#pragma omp simd

for (int i=0; i<size; ++i)

{

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}The vectorised loop was about four times faster on my computer than the standard loop (also called the “scalar” loop). The difference in speed between the vectorised loop and the scalar loop on your computer may be different.

The vector loop is faster than the scalar loop because, in the scalar loop, each iteration was performed serially, one after another. This meant that the calculation of the sum of

c[20] = a[20] + b[20]was performed after the calculation of

c[19] = a[19] + b[19]which was performed after the calculation of

c[18] = a[18] + b[18]etc. etc.

This fits in with our traditional view that a single core in a computer processor can only perform one floating point calculation at a time.

However, this view is not strictly correct. A single compute core can actually perform many floating point calculations simultaneously. The compute core achieves this by batching the floating point calculations together into groups (called vectors), and performing the entire group of floating points calculations at once using a vector floating point instruction. In the case of my computer, the compute core batched the floating point additions together into groups (vectors) of length 4. This meant that the four additions for

c[0] = a[0] + b[0];

c[1] = a[1] + b[1];

c[2] = a[2] + b[2];

c[3] = a[3] + b[3];were all performed simultanously. Then,

c[4] = a[4] + b[4];

c[5] = a[5] + b[5];

c[6] = a[6] + b[6];

c[7] = a[7] + b[7];were next all performed simultanously.

The vectorised loop was therefore four times faster, as the processor compute core performed four additions at once for the vectorised loop, in the same time as the scalar loop performed just one addition.

What is happening inside the processor?

So, how does a processor compute core perform multiple floating point additions at the same time?

Floating point processing…

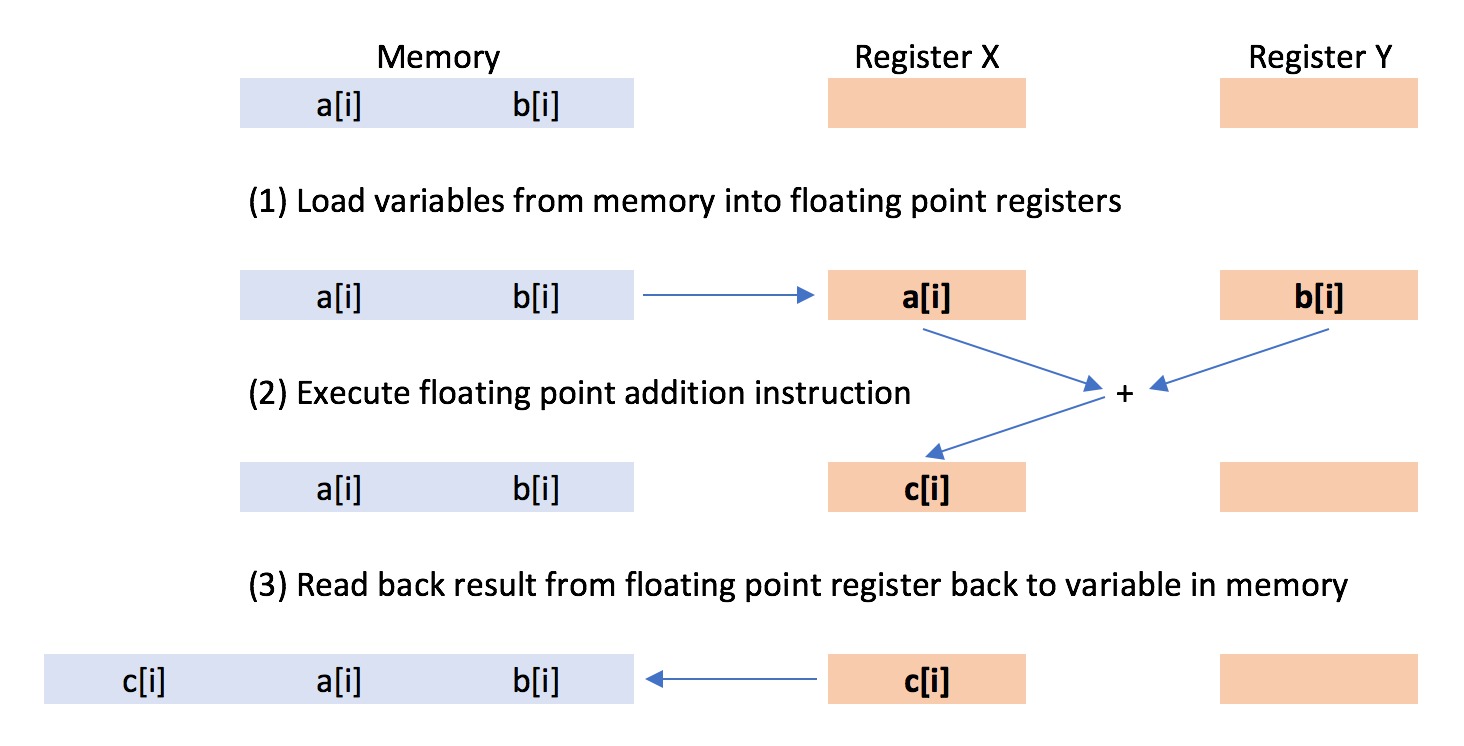

In normal use, arithmetic floating point calculations, such as addition, are performed using the floating point processing unit (FPU) built into each processor core. Floating point numbers are loaded onto a register in the floating point processing unit, and an arithmetic operation is performed on those numbers in response to the processor issuing a floating point processor instruction.

The floating point unit can perform a range of arithmetic operations in response to different arithmetic instructions, e.g. addition, multiplication, division etc. The size of the registers in the floating point unit determines the maximum size of the numbers that can be loaded into the unit, thus determining the maximum precision of the arithmetic calculation.

Most modern processors have floating point units with 64 bit registers. This means that floating point calculations can be performed with a maximum of 64 bits of precision. 64 bits (8 bytes) is commonly called “double precision”, and is what is normally used in C++ when we create a double variable. The floating point unit can also perform arithmetic operations using less precision, e.g. 32 bits (4 bytes). 32 bit precision is commonly called “single precision”, and is normally used in C++ as the float variable.

In the standard loop;

for (int i=0; i<size; ++i)

{

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}the two 32 bit floating point numbers a[i] and b[i] were loaded onto two 64 bit registers of the floating point unit. Once the numbers were loaded, the processor issued a “floating point addition” instruction, which instructed the floating point unit to add the two numbers together. This one floating point instruction caused a single addition to take place, to give the result c[i].

Vector processing…

In the vectorised loop, floating point operations were performed using the vector processing unit (VPU). A vector processing unit is similar to a floating point unit, in that it has registers on which you load numbers, and it performs arithmetic operations in response to instructions.

The difference is that the registers on a vector unit are much larger, e.g. 128 bits (16 bytes), 256 bits (32 bytes) or 512 bits (64 bytes). Rather than using this increased size to support higher floating point precision, this larger size is used to pack multiple floating point numbers together, so that multiple arithmetic operations can be performed in response to a single instruction.

Vector processing units are built into most modern processors, and typically they come with a fixed size. On my computer, the vector register is 128 bits. This means that it can hold four 32 bit floats, or two 64 bit doubles.

In the vectorised loop;

#pragma omp simd

for (int i=0; i<size; ++i)

{

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}two vectors of four 32 bit floating point numbers a[i] a[i+1] a[i+2] a[i+3] and b[i] b[i+1] b[i+2] b[i+3] were loaded onto two 128 bit vector registers of the vector processing unit. Once the vectors were loaded, the processor issued a “vector floating point addition” instruction, which instructed the vector processing unit to add the two vectors of numbers together. This one vector instruction caused four additions to take place, to give the results c[i] c[i+1] c[i+2] c[i+3].

On X86-64 processors (i.e. those produced by Intel), the vector processing unit is also called the SIMD unit. SIMD stands for “single instruction, multiple data”, referring to the fact that a single vector instruction results in arithmetic operations being performed simultaneously on multiple numbers (data).

The capabilities of the SIMD unit has evolved with each new generation of processors, and has gone through several standards;

- SSE - This stands for “Streaming SIMD Extensions”, and became available with the Pentium 3 processor in 1999. The vector registers are 128 bits in size. This means that an SSE-capable processor can perform four 32 bit float operations for every vector instruction, or two 64 bit double operations.

- SSE2 - This was a refinement of SSE, available since the Pentium 4 in 2001. The vector registers are 128 bits in size. All X86-64 processors support SSE2.

- SSE3/SSSE3/SSE4

- These are subtle extensions to SSE2 first made available in processors released between 2004-2006, which added more esoteric arithmetic operations.

- AVX - This stands for Advanced Vector eXtensions, and first became available on Intel processors from early 2011. This was a major upgrade over SSE2, as it doubles the size of the vector register from 128 bits to 256 bits. All AVX-capable processors fully support all versions of SSE. AVX-capable processors can perform eight 32 bit float operations for every vector instruction, or four 64 bit double operations.

- AVX2 - This is a subtle extension of AVX.

- AVX-512 - This is a major upgrade over AVX as it doubles the size of the vector register from 256 bits to 512 bits. This became available in Xeon Phi in 2016, and will become available in new Xeon processors from 2017. AVX-512-capable processors can perform sixteen 32 bit float operations for every vector instruction, or eight 64 bit double operations.

Why do processors have vector units?

As you can see, the trend is for the vector register to double in size every five-ten years. Why is this the case? The answer is a mix of economics and physics. Processors are marketed and purchased based on the number of floating point calculations per second (floating point operations - FLOPs) that they can perform. The more FLOPs, the faster the processor, and so, the market says, the better the computer.

The number of floating point calculations that can per performed per second is limited by the number of instructions that can be issued by the processor, which is limited by the clock speed of the processor. A 2.6 GHz processor can issue up to 2.6 billion instructions per second, and so can perform up to 2.6 billion floating point operations per second on the FPU (2.6 gigaflops).

One way to increase the number of flops would be to increase the clock speed. However, physics means the higher the clock speed, the hotter the processor and the more energy it will consume. Doubling from 2.6 GHz to 5.2 GHz is not energy efficient, and the processor would run at a temperature that it would likely melt.

If we rule out increasing the clock speed, then another way to increase the number of flops of the processor is to increase the number of processor cores. Twice the processor cores means twice the number of floating point units, and so twice the number of FLOPs. Moore’s Law highlights that the number of available transistors in a given area of processor will double every 24 months. Processor manufacturers use these extra transistors to duplicate the design for the processor core, such that the number of cores printed on a processor roughly doubles every few years. Hence now dual-, quad-, oct- or hexa-deca- processors are common, and programmers need to learn how to write parallel programs… (e.g. see my parallel C++ course). However, increasing the number of cores in a processor is not quite as easy as copying and pasting a proven design, and as a hexa-deca-core 2.6 GHz processor can still only perform sixteen floating point operations per clock cycle, even this is limited to 16 x 2.6 GHz = 41.6 gigaflops.

Increasing the size of the vector unit thereby provides perhaps the easiest way to increase the number of FLOPs. Doubling the size of the vector register doubles the number of FLOPs that can be performed per instruction, and thus per clock cycle. A single core of a 2.6 GHz processor can perform 2.6 gigaflops on the floating point unit, but 8 x 2.6 = 20.8 gigaflops of floating point calculations on the AVX2 vector unit. Such processors can be bought today with up to 16 cores, meaning that the full hexa-deca-core processor can perform 8 x 8 x 2.6 = 332 gigaflops of floating point calculations using the AVX2 units. A 332 gigaflop processor is easier to sell than a 2.6 gigaflop processor, and is rewarded by the market with higher purchases and higher volumes. However, your program can only achieve 332 gigaflops if it uses all sixteen cores and bacthes all floating point calculations into vectors of 16, so to make the best use of the vector units. Otherwise, 2.6 gigaflops is the most you can hope for…

This trend will continue. The latest Xeon Phi has 72 cores running at a clock speed of 1.5 GHz, and has AVX-512 vector registers. This means that it can deliver at least+ 1700 gigaflops (1.7 teraflops) of floating point power… assuming you have a sufficiently parallelised and vectorised code. If not, then your code will be ~1000 times slower, and only able to reach 1.5 gigaflops.

Automatic vectorisation, like automatic parallelisation is too difficult for a C++ compiler to perform. Thus, just as we now need to learn how to parallelise their programs, so we also need to learn how to vectorise our codes.

+Note that there is even more cleverness that pushes up the number of theoretical floating point operations you can perform per second (which you may or may not be able to access). Search for “vector fused multiply add", and “hyperthreading" if you want to know more. Also note that these theoretical “peak performance” numbers do not account for any of the clock cycles needed to load and unload data to and from the vector registers and main memory, or account for the processor temporarily increasing clockspeed (“turbo boost”) or even reducing clockspeed (“downclocking”) depending on how hot or cold they are, and how much cooling is available.

Exercise

Find out the speed, number of cores and size of vector of the processor you are using now (e.g. by using the

lscpucommand on Linux, and multiplying the number of sockets by the number of cores per socket, and then looking at the file/proc/cpuinfoand seeing ifsse,sse2,avxoravx2etc. are included in the set of supported processorflags).Work out the theoretical maximum number of floating point calculations per second (FLOPs) you could perform using a serial (non-parallel), scalar (unvectorised) code.

Next, work out the number of FLOPs for a fully-parallel, scalar code.

Next, work out the number of FLOPs for a fully-parallel, fully vectorised code.

Is the speed-up from vectorisation and parallelisation worth pursuing?